We moved my 91-year-old mother on Friday morning, I presided at a memorial service Saturday morning, and led Bridge St UC worship on Sunday. Still, I managed to see six documentaries at this year's Docfest in Belleville. All were good, but two stood out because they were about First Nations issues in Canada, and our United Church continues to sort out our miserable past with Native peoples and attempts to chart a more respectful and collaborative future.

Angry Inuk is filmmaker Alethea Arnaquq-Baril 's attempt to get the story of Inuit seal-hunters heard. Even though baby seals --white coats -- haven't been hunted in nearly four decades their images are used to fight for the rights of seals. No seal species is endangered either, while more than a thousand other creatures are. But because seals seem cute animal protection agencies keep them front and centre. Why? They are money-makers for these organizations, although Greenpeace has recently apologized for the effect that anti-sealing efforts have on Inuit livelihood.

The argument Inuit peoples around the world make is that if they are hunting the seals for food, which the European Union endorses, why can't they make and sell skin products rather than leaving them to rot? Producing clothing is part of traditional culture as well. As people point out in the film, somehow it's okay to wear a leather coat or shoes, or a jacket made out of fossil fuels (what do you think Gortex is?) but not from sealskin. Meanwhile, people of the North pay many times more for food from the south than we do but can't make a decent living. Incomes have dropped dramatically since the EU banned seal products.

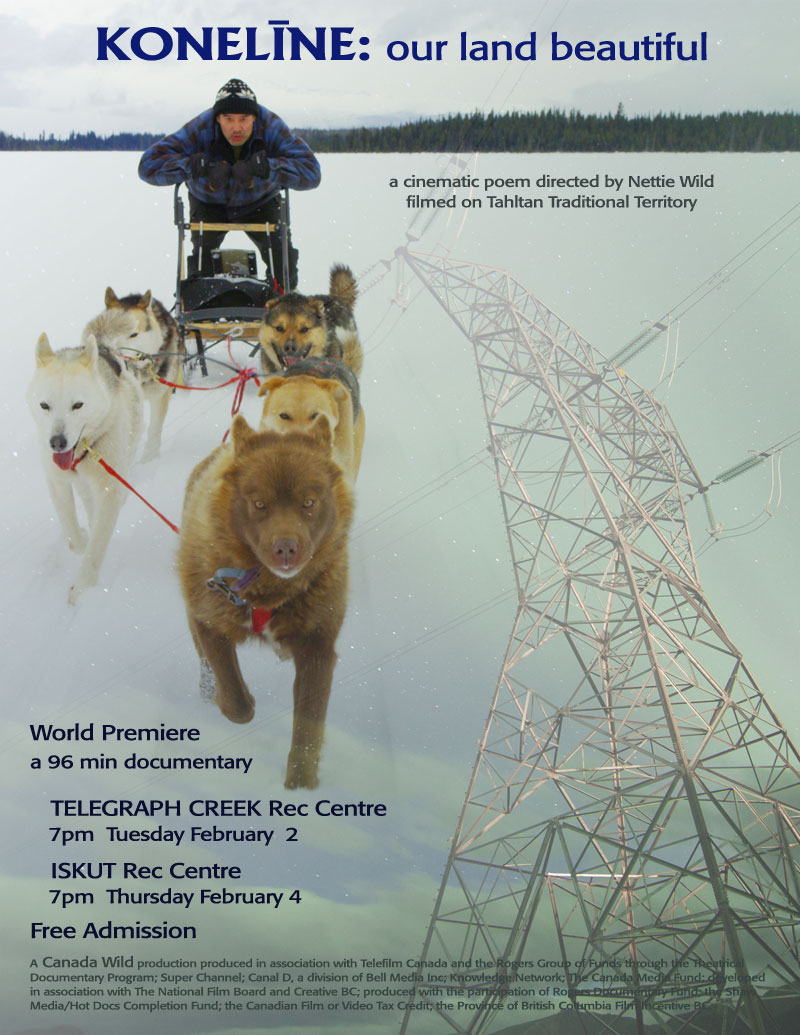

The other film is called Konaline (Cone-a-lean-ah) which means "our land beautiful" and "cognitively beautiful" in the Tahltan language of Northern BC. I can't stop thinking about the exquisite beauty of this doc, along with the powerful and balanced storytelling. While Nettie Wild offers a paen to a demanding way of life for the people of this region she doesn't paint those who are developing a copper and gold mine as villains. I was struck that there is no word for wilderness in Tahltan. This is simply the land on and in which they live.

I left both these exceptional films feeling quite emotional. What have we really learned about our relationships with First Nations peoples? Are we just paying lip service when we apologize for past wrongs but continue to perpetuate injustices? What are we called to do as individuals of faith and faith communities?

Thoughts?

No comments:

Post a Comment